Radical Object-Orientation #09: Dependencies as a Matter of Abstraction

These are the "good guys"

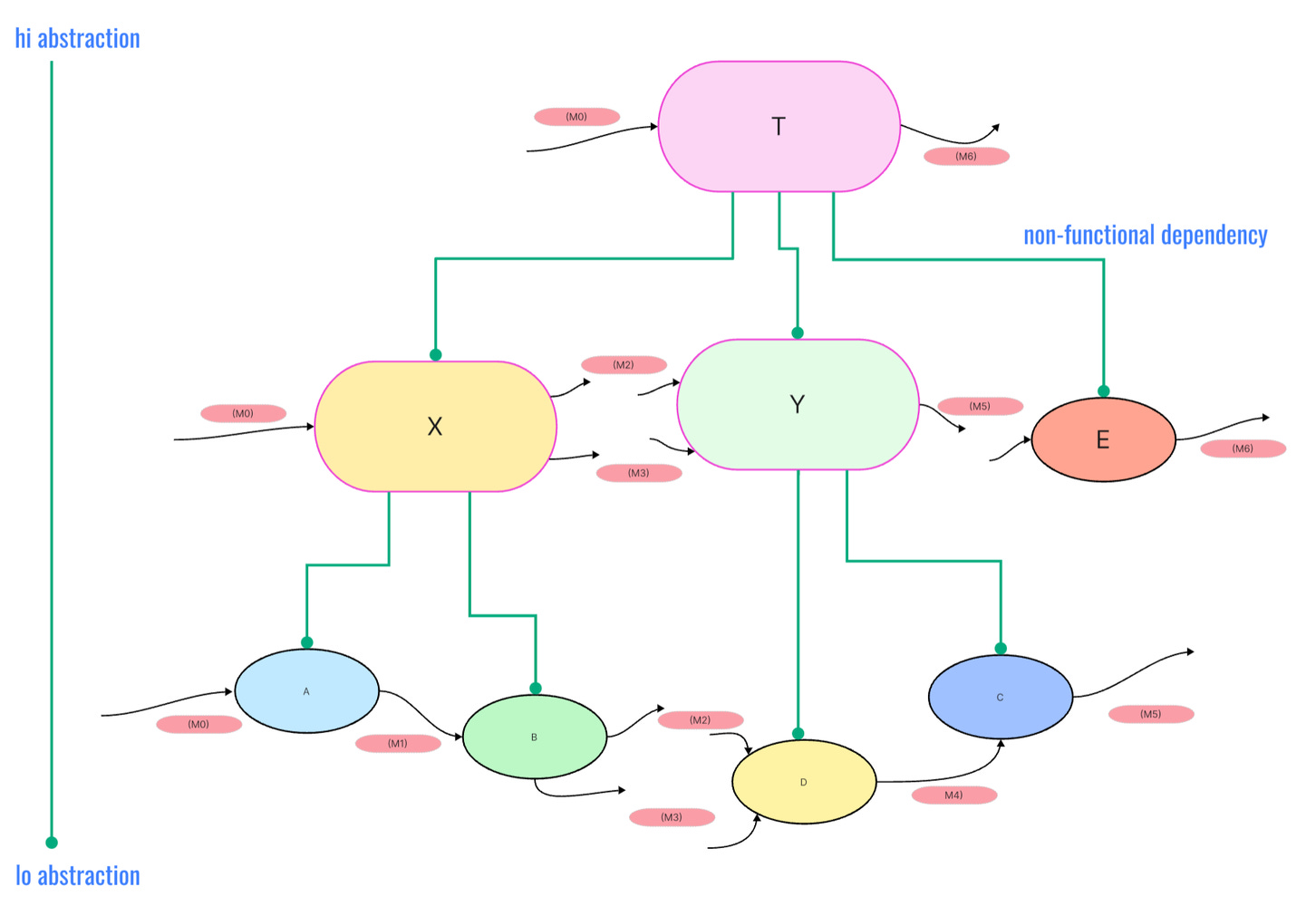

Radical Object-Orientation clears away functional dependencies, making testing and understanding a whole lot easier.

But dependencies still exist; they're just not functional. It's not about one object's logic depending on another's.

Integrations depend on the functional units they combine, whether those are operations aka objects or other integrations. But integrations don't do anything on their own. Their job is simple: they just connect functional units into data flows.

Within such a data flow, a functional unit must be present and do its job. The entire data flow depends on it. But this isn't the same as a dependency between objects, which can have very complex tasks.

Data flows are much easier to grasp. You don't need to dive deep into the hierarchy; you read them from left to right. They describe their function fully at a glance, on a single level of abstraction.

Data flows hardly need testing. Well, almost. They're so straightforward. Integrating functional units is a breeze. Okay, that might be stretching it, but that's the gist. Data flows require far fewer tests because there are fewer paths within them. And if the integrated functional units are correct, then the integration will work too. You might want to verify this with so-called integration tests now and then; you'll want to feel how the integrated functional units work together. But that's nothing compared to the effort required to test operations.

So, the dependencies of integrations on integrated functional units are relatively harmless. No need to fear them. On the contrary: They are essential for abstractions. The abstract always builds on the detail; the whole always depends on its parts.

In Radical Object-Orientation, there's a rule:

Dependencies between functional units only run from higher to lower abstraction.

Dependencies point down the abstraction gradient. That’s what the Dependency Inversion Principle (DIP) was about all along. But why limit abstractions to interfaces as it’s mostly the case in DIP examples? Integrations are abstractions as well.

This gives you a great test: Whenever you see a dependency in your code, ask yourself whether the dependent is at a higher level of abstraction than the independent.

If yes, then the dependency is fine. If not, then your structure doesn't yet follow the IOSP of Radical Object-Orientation and does not implement a stratified design.

Take, for example, the dependencies in the "layered architecture" pattern. Here, the presentation layer depends on the business logic layer, which depends on the data access layer.

But is the presentation layer more abstract than the business logic layer, and the latter more abstract than the data access layer? No. They all operate at the same level of abstraction. They all do something completely different; their tasks are complementary.

When following the IOSP, essentially the same thing happens in every stratum, just at a different level of abstraction.

This means, in the layered model, the dependencies are functional. The layered model doesn't align with radical object orientation. That's why code in a layered software architecture is so hard to test. That's why there's so much talk about Inversion of Control (IoC), interfaces, and test surrogates.

The layered model doesn't handle dependencies well.

Dependencies aren't "evil"; you can't avoid them. They're like friction in mechanics: no machine works without friction. But you have to handle them carefully. For dependencies, this means: avoid functional dependencies, seek non-functional dependencies along the hierarchy of abstraction.

And now we're at a point where you should finally ask: What's actually being connected in these data flows and integrations? For Alan Kay, it's objects. But unfortunately, this concept doesn't scale very well.