Radical Object-Orientation #07: Nesting Integrations

Objects are operating in a hierarchy of data flows

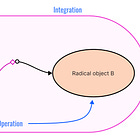

Integration is what connects objects together into a new whole. Through integration, objects become partners in cooperation - even if they are unaware of each other (PoMO). Integration maintains their independence. Integration is quite different from the activity of objects and must be fundamentally separated from it (IOSP).

These are the core principles of Alan Kay's idea of object orientation for me, aka Radical Object-Orientation.

Objects communicate with unidirectional messages for a purpose that is larger, more comprehensive. They are parts of a whole. The whole is established and represented by integration.

But here's the kicker: From the outside, integration itself is indistinguishable from an object.

An object processes incoming messages into outgoing messages by leveraging its internal state.

Connected objects also process incoming messages into outgoing ones. They do this in a data flow, which you can think of as a production line. A message triggers a cascade of messages within the data flow at the first object, leading to messages at its end.

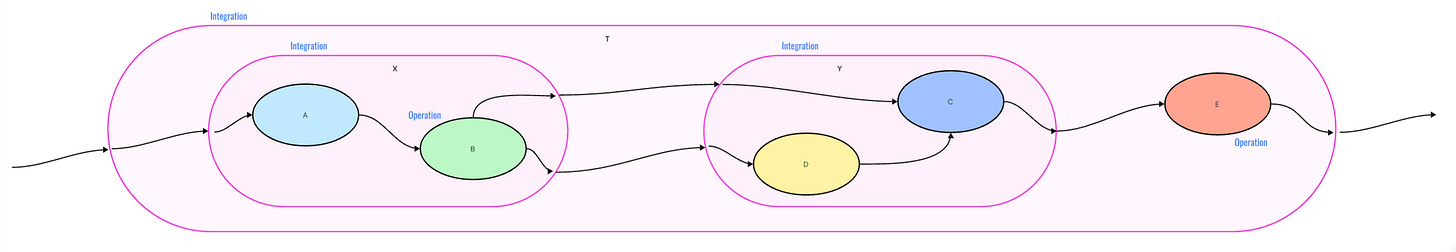

This means that the integration of objects behaves as a black box just like the individual objects it integrates. Integrations and their operations are in a whole-part relationship. Yet, it's evident that integrations are also parts of an even larger whole. Integrations can be integrated along with operations and other integrations. It’s a hierarchy of integrations with objects at the bottom.

The Integration Operation Segregation Principle (IOSP) allows for arbitrarily deep nesting downwards or abstraction upwards.

With each integration, complementary functional units - integrations or operations - are connected into a new whole within a data flow. The higher you go in such a hierarchy, the easier it becomes to initiate behavior with a message. And the higher you go, the more specialized and specific the integrations become.

An integration hierarchy reflects what constitutes our prosperity: a hierarchy of technological abstractions. Today, you get into a car and simply press a button to start it. Compare this convenience to the effort required to start a motor-driven vehicle 120 years ago. Or take your smartphone and make a call. Compare that with the effort needed to make a call 100 years ago.

You are surrounded by hierarchies of integration. You live at the peak of a deep hierarchy of abstractions.

This idea is not new, however. It was already described as a hierarchy of languages in the 1980s.